As I sit here writing this on my sleek new Macbook Pro, my six year old daughter, Lily, is sitting on the living room floor banging away at the Smith-Corona Coronet electric typewriter I purchased yesterday. It was an incredible find: $6.99 at the Brockport Goodwill, in pristine condition, with the original case. The ribbon is fuzzy and faint, but after a quick search on ebay, we discovered that fresh, brand new ribbons are still available. I ordered several.

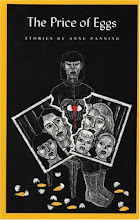

I wrote many of the stories in my first book, The Price of Eggs, on an electric typewriter. I was living in Minneapolis at the time, newly returned from Peace Corps, had no car and no meaningful employment. I took the bus one day to Montgomery Ward's in St. Paul, and bought the pumpkin-colored machine, riding home with the heavy case warm on my lap like a small child. I loved that typewriter, and spent hours in the attic of my rental house pounding out stories while I looked out into the treetops.

Years later, I joke that I now have a "museum" in my attic here in Brockport, but it's actually true. On an old table up there, I am the keeper of old telephones, landmark newspapers such as 9/11 and Obama's inauguration, Fisher Price toys, metal hair dryers, floppy disks—anything that I feel is either already defunct or soon on its way.

I realize this photo might suggest that I should possibly be tapped for an A & E "Hoarders" intervention, but in my defense let me say that the last time I brought my kids up to the "museum," my nine year old son, Hudson, asked if he could take the 9/11 newspaper to his room and read it. I said yes. His whole world changed that day. For years we'd been telling him how he was just a baby when it happened, and how we remember him lying on a blanket that morning in front of the TV. Now it has become real to him, and has shifted his taste in reading towards historical nonfiction—the power of history you can hold in your hand.

But back to the newly acquired electric typewriter.

Lily said to me this morning, "I like how it dings." I said yeah, me too. She continued: "Doesn't it sound like I'm slapping it? But I'm not. I'm just pressing." I smiled, and remembered how physical writing used to feel to me. There was great thunderous noise associated with writing: the deep rumble and vibration of the engine, the punch of the keys, the ding of the bell, the zip of the carriage, the definitive echo of the final period.

The first story I ever published, "Pigs," was revised 13 times. Each draft had to be re-typed in full every time. There was a fine Braille texture to those pages; sometimes punctuation would even break through the page and create black holes. I remember rocking slightly when I was in a good writing groove. Writing felt more deliberate then. You had to commit or go back and completely redo a page. Not so now, where you can futz around with font, cut & paste, pretend you're revising when really you're just editing and tinkering. Revising, after all, means "re-vision":

to see again newly and clearly.

This is the machine to do it. It beckons me: come back, come back.

.jpg)